Ammonia Cakes

/You’ll find this recipe in:

The New Galt Cook Book

Compiled and Edited by: Margaret Taylor and Frances McNaught

Toronto, 1898

Added later: If you’re interested in learning more about Baker’s Ammonia or Ammonium Bicarbonate, continuing reading after this recipe to find out some history and background about this leavening agent.

If you’re more interested in baking a delicious cookie that uses Baker’s Ammonia, head over to my Cup Cookies recipe (they taste better than this Ammonia Cakes recipe).

Original Recipe:

AMMONIA CAKES.

MISS ROOS, WATERLOO.

Half pound white sugar, half a pint sweet cream, one egg, half ounce ammonia, a small piece of butter (half the size of an egg). Flour enough to roll out.

My Recipe:

1 cup white sugar

1 cup cream

1 egg

3 tbsp softened butter

1 tbsp + 1 tsp baking ammonia*

3 ½ cups flour

* Baking ammonia is a white powder and it is also sometimes called ammonium bicarbonate, hartshorn or hirschhornsalz

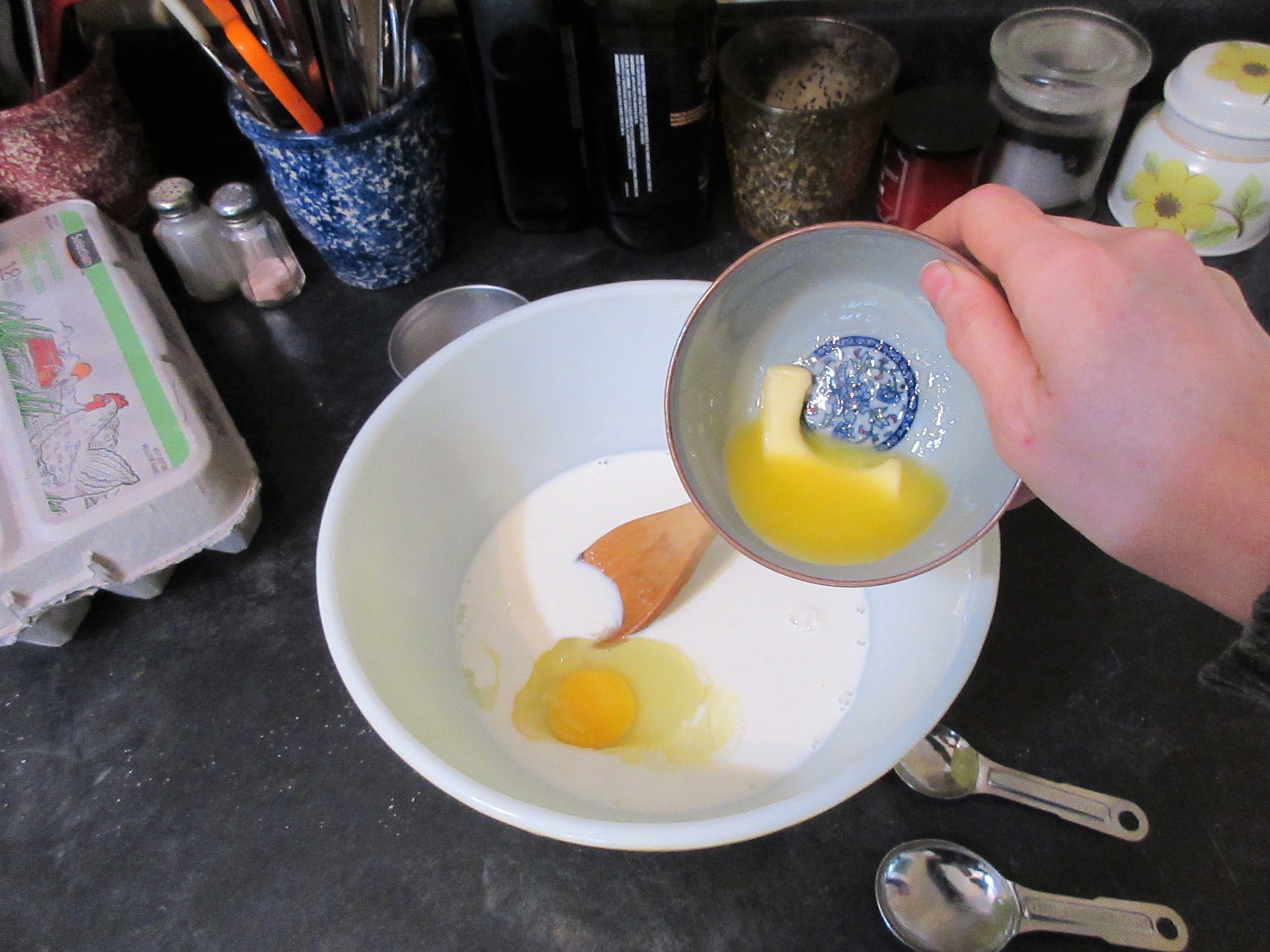

1) Mix together the sugar, cream, egg and butter, then add the baking ammonia and the flour. You may need to use your hands to fully combine the ingredients.

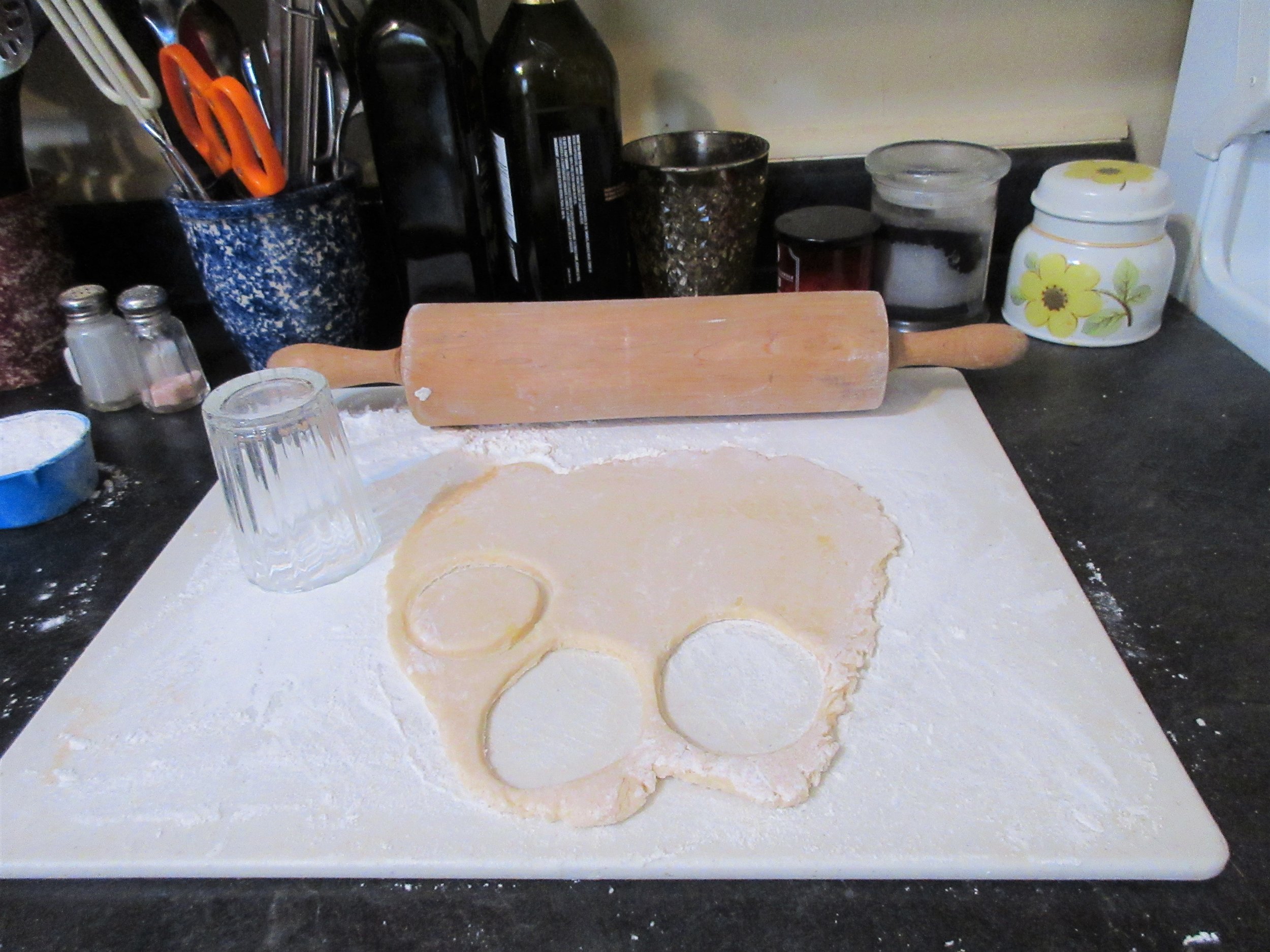

2) Preheat the oven to 350 F (175 C) while you roll and cut out all the cookies. Place the cakes on cookie sheets, then put them all in the oven at once. After a few minutes, you’ll start to smell a strong ammonia odour. The cakes are done when you open the oven door and smell cookies instead of ammonia, which should be about 15 minutes. This recipe made about 5 dozen 2 inch (5 cm) cookies.

A couple of weeks ago, I prepared the food served at a Victorian Tea held at the Fashion History Museum in Cambridge, Ontario. All of the recipes served came from The New Galt Cookbook, a Cambridge-area community cookbook published in 1898. Food Historian Carolyn Blackstock spoke during the Tea about her experience in 2014 when she made a recipe a day for a year from The New Galt Cookbook. Yes, amazingly she made 365 recipes and wrote about each one. I sometimes struggle with pulling off 2 or 3 blog posts a month.

Ammonia Cakes were on the menu, and to be honest, it’s one of my least favourite recipes served at the Victorian Tea. I certainly wasn’t planning to make them again, but when everyone was packing up afterwards, things changed. Johnathan, the Curator at the Fashion History Museum, said to me: “Julia, we’d like to present you with a parting gift.” He handed me the rest of the baking ammonia and announced that he would absolutely never make anything with it in the future!

I had never baked with Ammonium Bicarbonate as a leavening agent before, but thankfully Carolyn Blackstock explained the basics in her blog post about Ammonia Cakes. As I noted in my modern interpretation of this recipe submitted by Miss Roos, you will know when the cakes are in the process of being baked because your oven will stink like ammonia or cat urine. Eventually, you’ll open the oven door and only smell the aroma of delicious cookies. That’s how you know when Ammonia Cakes are baked.

After we had three trays of Ammonia Cakes in the oven when we were baking for the Victorian Tea, we realized that we wouldn’t be able to smell when they were done because we had put in the cookie sheets at different times. We solved the problem by firing up all the ovens and placing one tray in each oven. I suggest that you put all your trays in the oven at once, then you’ll be able to accurately follow your nose.

This form of ammonia is sometimes called Baking Ammonia, Baker’s Ammonia, Ammonia Carbonate, Ammonia Bicarbonate, Hartshorn or Hirschhornsalz. Not being familiar with baking with ammonia, I did some research about its history. These days, it is commonly found in traditional German or Scandinavian baking such as cookies, biscuits or crackers. In other words, any baking that is thin. If ammonia bicarbonate is used in something with more depth like a cake, the ammonia created when baking occurs wouldn’t be able to escape from the centre and the baking would taste disgusting. Baking risen with ammonia is light, crisp and keeps its form, so it’s especially good for moulded cookies like Springerle.

Baker’s Ammonia first started being used in the Middle Ages, but it rose in popularity during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Originally, deer antlers were ground down and dry distilled in kilns. A British term for a stag is “hart” and “hart’s horn” eventually transformed into Hartshorn. In German, Hirschhornsalz translates to staghorn salt. Hartshorn was used as a smelling salt for fainting and was also used medicinally for diarrhea, fevers and a variety of bites.

The area surrounding Kitchener-Waterloo (which is next door to Cambridge) has a large German immigrant population and each October, Kitchener-Waterloo hosts the largest Oktoberfest celebration outside of Bavaria. Our Ammonia Cakes recipe was submitted by a Miss Roos of Waterloo, who most likely had German roots. One of the fascinating aspects of Carolyn Blackstock’s New Galt Cook Book project is that she not only made a recipe a day, but she also did research about the women who submitted the recipes. Many days, she provides details and pictures about that woman’s life, but unfortunately without knowing her first name, the identity of Miss Roos remains a mystery. Carolyn does present a few possibilities in her blog post, though.

If you’ve read all this and are wondering why anyone would use ammonia bicarbonate instead of sodium bicarbonate, baking soda wasn’t produced as a leavening agent until 1846. This Smithsonian Magazine article about the history of Baking Powder is a great place to start if you want to find out more.

I’ll end by clarifying why I’m not in love with Ammonia Cakes. It’s not because they taste bad. I assure you that they don’t taste like ammonia! They aren’t my favourite because they don’t have much flavour. Aside from historic baking, I don’t eat much refined sugar in my regular life so if I’m eating something with sugar in it, I want it to taste GOOD and Ammonia Cakes just tasted bland and boring to me. I also had almost 5 dozen of them and I prefer to give delicious food to others, rather than feeling like I need to apologize for the recipe.

I thought that if I could find a recipe for a thin icing that hardens from the 1890s, that would improve the taste and it turned out to be a very successful solution. I didn’t have to look far for this icing recipe. I just looked at Carolyn Blackstock’s blog and found Icing for Cake, also from The New Galt Cook Book. I made the icing and iced the Ammonia Cakes the next day, which transformed them from bland to shablam!